A Legacy Reawakened and the Multifaceted Effort to Share, Study, and Celebrate Her Work

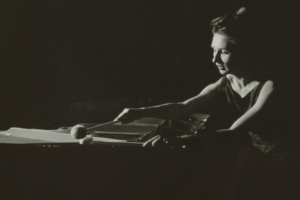

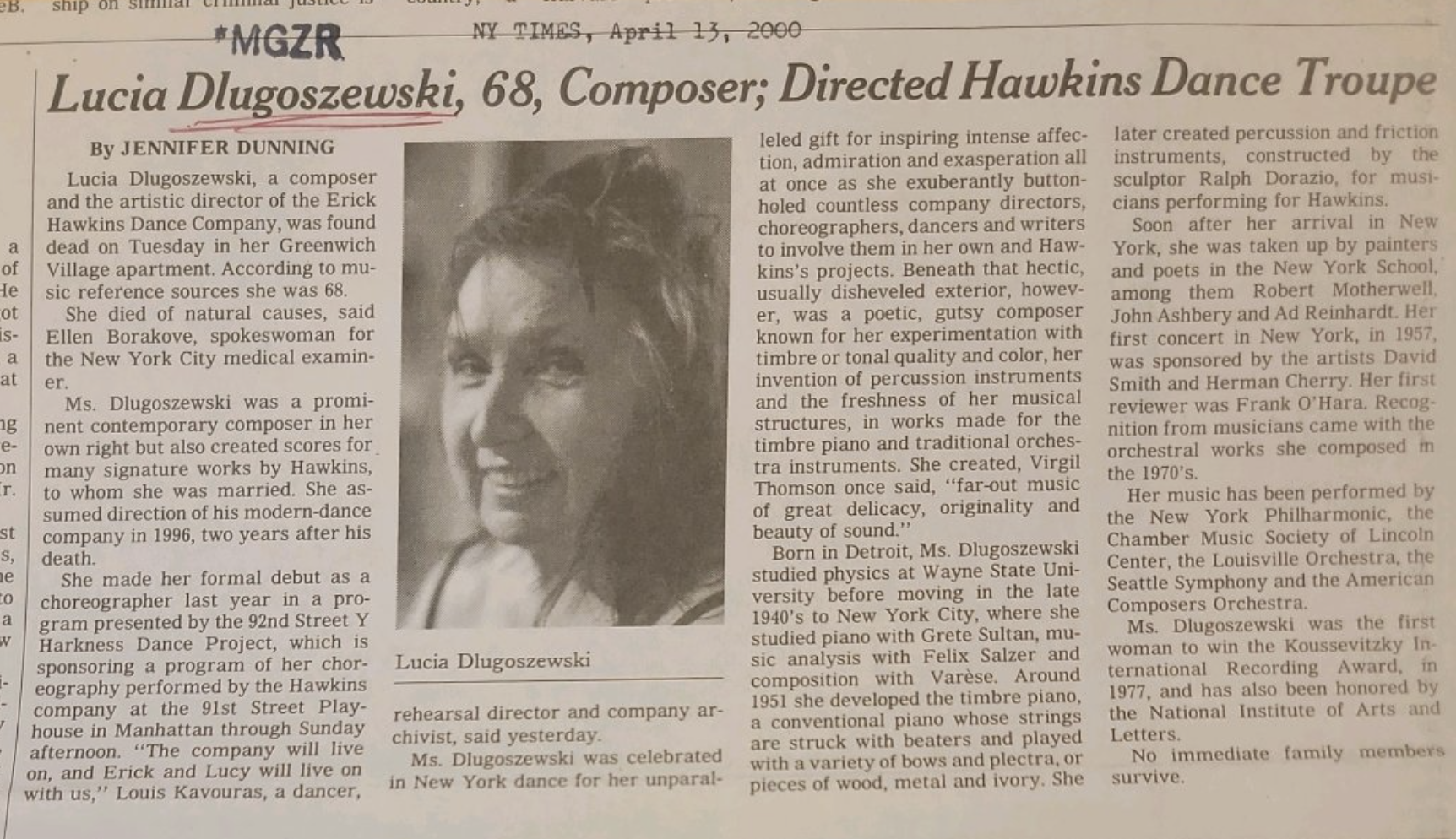

In the vast, shifting landscape of contemporary classical music, certain figures loom large while others fade from view, their contributions obscured by time, institutional neglect, or the structural biases of artistic canonization. One such figure is Lucia Dlugoszewski (1925 – 2000), a composer, musician, writer, and choreographer whose work once resonated through the avant-garde circles of mid-century New York but whose name remains largely absent from the dominant narratives of twentieth-century music history. That absence, however, is beginning to change—just as the year 2025 marks the centenary of her birth, prompting a growing wave of attention from performers, scholars, and curators alike.

In the decades since her death, Dlugoszewski’s legacy has been shaped by limited access to her work—only a handful of published scores, few recorded pieces, and perhaps a shadow cast by her significant association with the Erick Hawkins Dance Company, which itself has sadly faded from prominence in historical accounts.

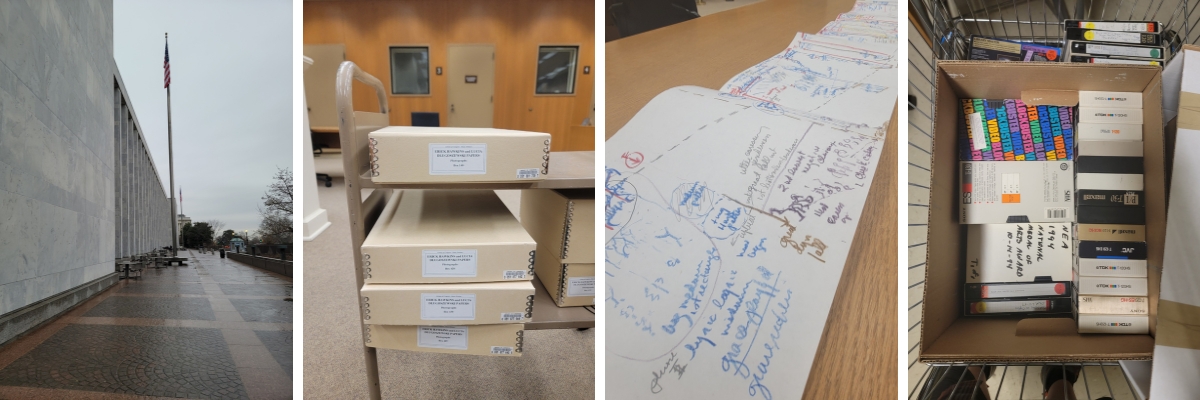

With her extensive archives now newly available through the Erick Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski Papers at the Library of Congress, interest in her work is steadily growing among performers and scholars. Additionally, Kevin Lewis’s 2011 dissertation, “The Miracle of Unintelligibility” provided a crucial foundation for understanding her music, and Amy C. Beal’s 2022 book, Terrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia Dlugoszewski has further catalyzed this renewed engagement, offering a deeply researched exploration of her career and artistic philosophy.

Since 2023, Dustin Hurt has immersed himself in the world of Dlugoszewski and her longtime associate Erick Hawkins. Building on his previous work reviving the legacy of Julius Eastman, Hurt, who is the founder and director of Bowerbird, has made dozens of trips to the Library of Congress, conducted research at numerous other archives, engaged in dialogue with an international network of performers, curators, and scholars, and conducted interviews with those who knew Dlugoszewski personally.

During this time, Hurt has developed a close working relationship with Katherine Duke of the Erick Hawkins Dance Company, whose deep institutional and personal knowledge of both Erick Hawkins and Lucia Dlugoszewski has significantly deepened his understanding of Dlugoszewski’s work.

A central focus of Hurt’s research has been to develop a comprehensive understanding of Lucia Dlugoszewski’s work, particularly her completed and performable compositions. This ongoing effort includes documenting unpublished scores, listening to archival recordings, researching and clarifying her notation, and working toward a broader understanding of the performance techniques integral to her Timbre Piano and extended percussion practice. By steadily expanding the body of knowledge surrounding her work, he aims to facilitate future performances and ensure her music’s continued presence on stage.

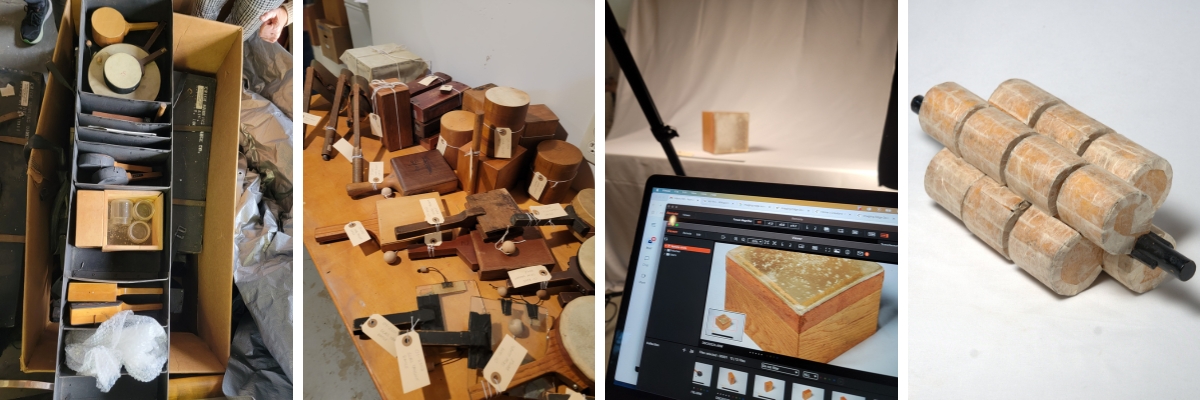

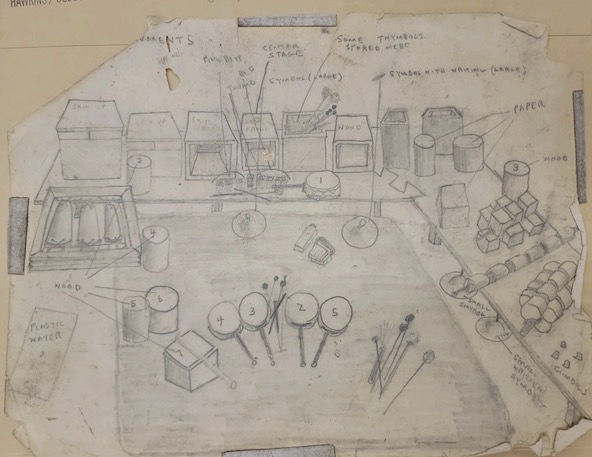

Closely related to his work on Dlugoszewski’s repertoire, Hurt has been studying her invented percussion instruments. With Katherine Duke’s assistance and in collaboration with percussionist Andy Thierauf, he has gathered and documented more than 200 of Dlugoszewski’s extant instruments. This research aims to not only document and preserve their unique construction and sonic possibilities but also to enable the creation of replicas for future performances.

Dlugoszewski’s compositions, once described as magic acts of impossible sound, will soon ring out in concert halls again. As a culmination of this chapter of rediscovery, Bowerbird, in collaboration with FringeArts, is presenting a two-concert survey of Dlugoszewski’s music that showcases the breadth of her artistic vision. A central part of these programs is a rare performance by the Erick Hawkins Dance Company, under the artistic direction of Katherine Duke, featuring Erick Hawkins’ original choreography performed live to Dlugoszewski’s music.

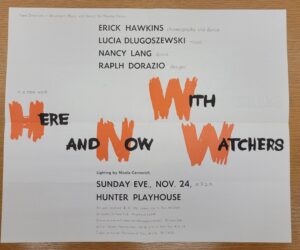

The concerts will highlight two of Dlugoszewski’s groundbreaking innovations—her timbre piano technique and her orchestra of invented percussion instruments. The timbre piano, a radical expansion of the grand piano’s sonic possibilities, will be explored in multiple works by Italian pianist Agnese Toniutti. Her invented percussion instruments, originally developed with sculptor Ralph Dorazio and reconstructed by Dustin Donahue, will also play a central role in the performances. The programs will feature performances by Network for New Music, Arcana New Music Ensemble, Either/Or, and Peter Evans, among others.

The phrase “Pure Lucia” comes directly from Dlugoszewski’s own writings, appearing throughout her notebooks as a kind of artistic mantra—an affirmation of staying true to her vision, pushing boundaries, and resisting external pressures. The same phrase was echoed by those who knew her personally; when recalling moments that defined her character, they would often say, “That was Pure Lucia.” This project adopts that name as a tribute to the authenticity, innovation, and uncompromising artistry that shaped her life and music.

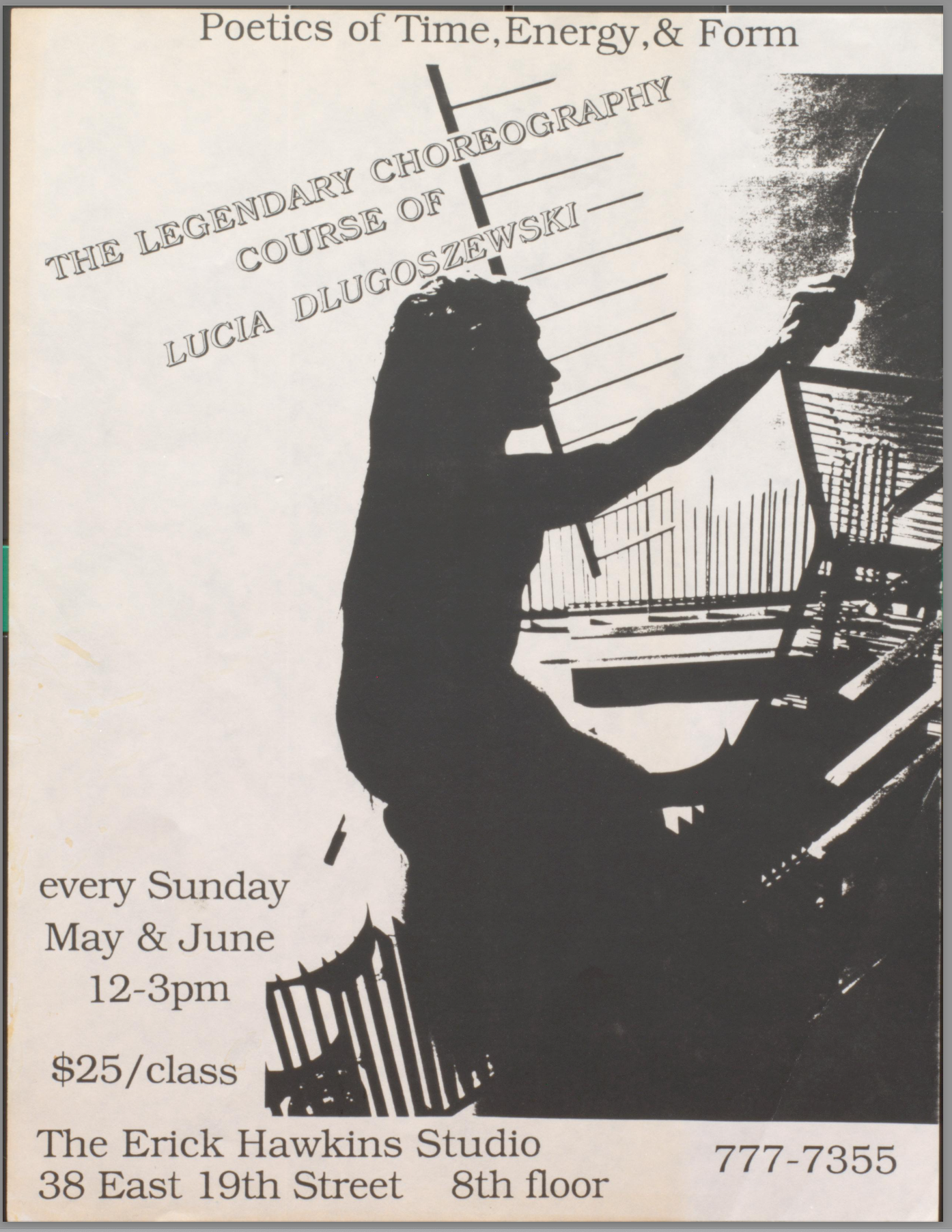

“Lunch with Lucia” is a web series of conversations exploring the music and legacy of Lucia Dlugoszewski. Featuring leading performers, scholars, and collaborators in conversation with Dustin Hurt, each session delves into a different aspect of her work—her groundbreaking timbre piano technique, innovative percussion instruments, compositions for brass and strings, and her deep connection to dance. Hosted on Zoom and open to the public, these lunchtime discussions offer a unique opportunity to listen, learn, and engage with the rediscovery of one of the most visionary yet underrecognized figures in 20th-century contemporary music.

Programs:

Mid-west Origins: Lucille Ruth Dlugoszewski

Born on June 16, 1925, in Detroit, Michigan, to Polish immigrant parents, Lucia Dlugoszewski (pronounced LOO-sha dwoo-goh-SHEF-skee) was immersed in the arts from a young age, playing piano, composing music, and writing poetry. She initially pursued studies in chemistry and pre-medicine at Wayne State University, but by the late 1940s, music had become her primary focus. Her birth name was “Lucille”, but in her twenties she opted to use “Lucia” instead.

In 1949, she was awarded a fellowship that brought her to New York City, where she studied piano with Grete Sultan and explored composition and theory under the guidance of Edgard Varèse. During this period, she also became acquainted with John Cage, who played an early role in shaping her engagement with the avant-garde community.

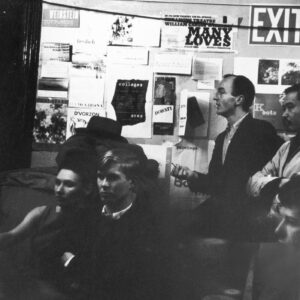

By the early 1950s, Dlugoszewski was deeply embedded in New York’s experimental arts scene—mixing with painters, poets, dancers, theater artists, and filmmakers in the loft concerts and underground venues of downtown Manhattan.

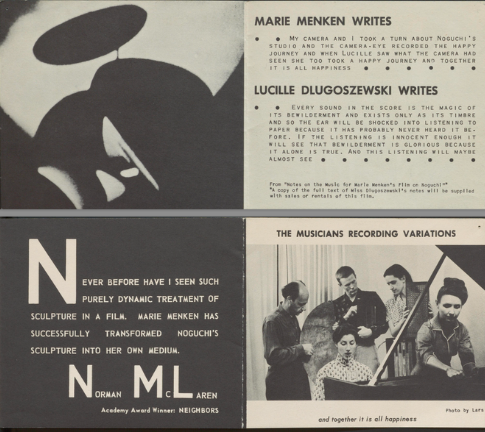

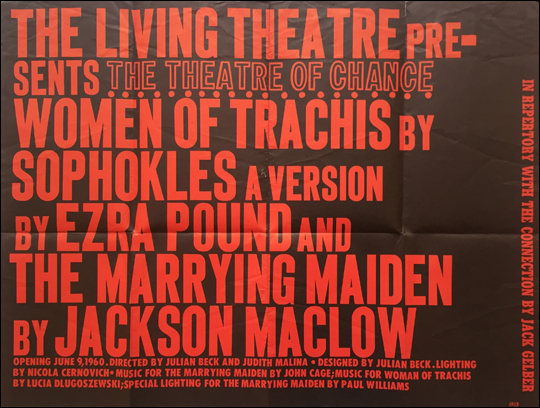

She collaborated with key figures in experimental theater, including Judith Malina and Julian Beck’s Living Theatre, and composed music for avant-garde films such as Jonas Mekas’s Guns of the Trees and Marie Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi. She was briefly part of Cage’s circle and engaged with the techniques of Henry Cowell and others working with extended piano techniques. But by 1952, she had begun developing a distinctive artistic voice, expanding beyond these influences into something uniquely her own.

New Frontiers: Timbre Piano and Invented Percussion

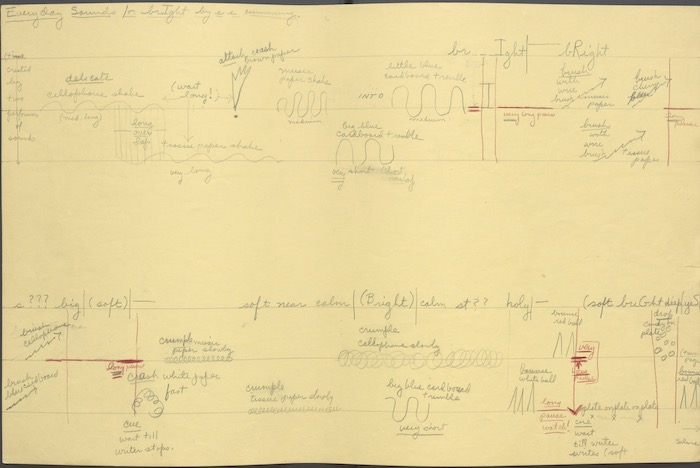

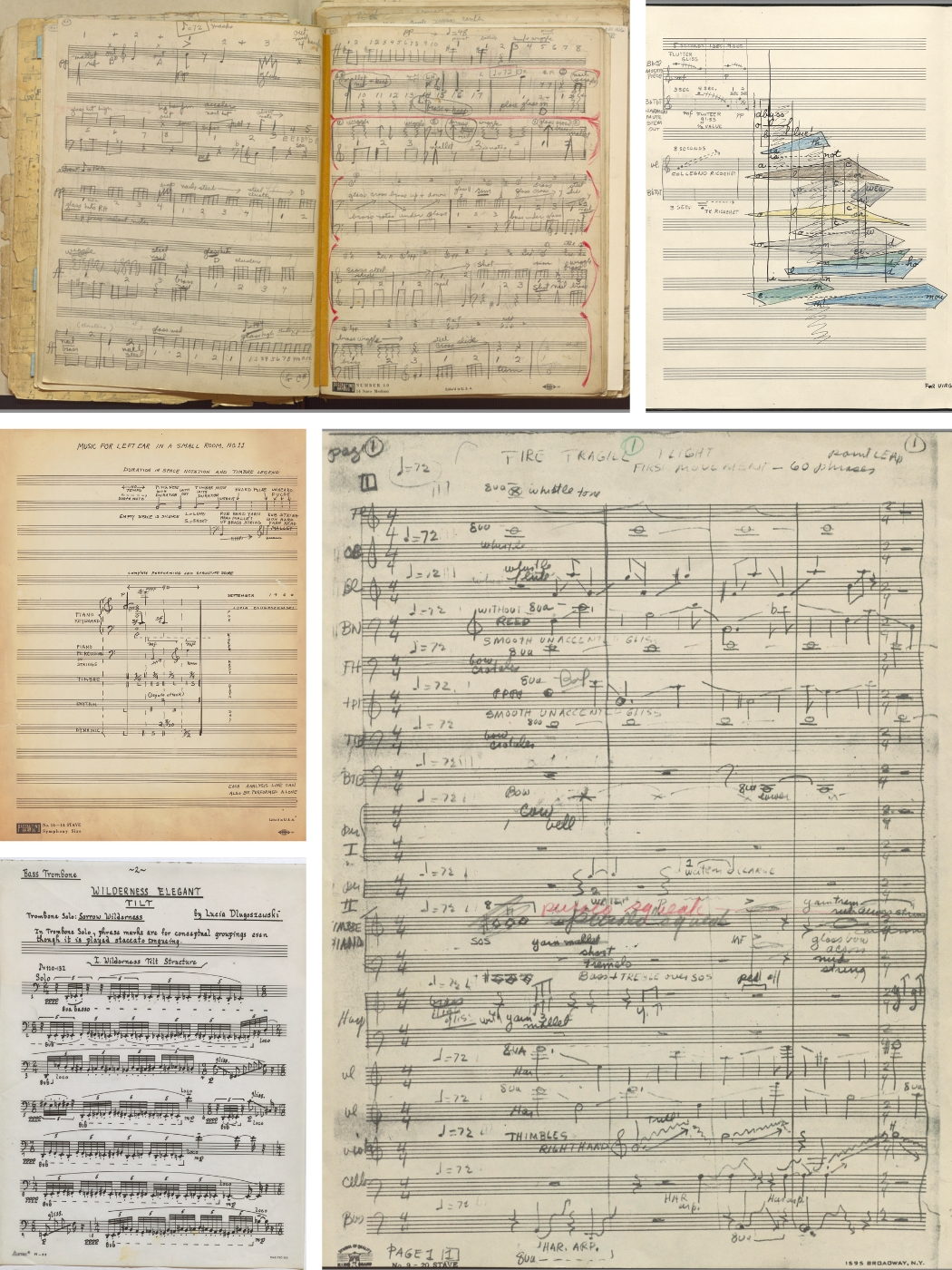

Dlugoszewski’s innovations in sound exploration took shape during these formative years. She developed what she called “Timbre Piano,” a performance practice centered on direct interaction with the strings and frame of the piano using mallets, objects, and other unconventional techniques. This approach differed from Cage’s prepared piano, which altered the instrument’s sound by inserting objects between the strings but largely retained the use of the keyboard for playing. Dlugoszewski’s fascination with sound extended beyond traditional instruments, focusing on what she called “everyday sounds.” She explored the sonic possibilities of materials like water pouring from one vessel to another, rice cascading onto a surface, and the subtle textures of paper tearing. This interest in everyday sounds paralleled the work of John Cage, whose 1952 piece Water Music also incorporated non-instrumental sound sources. However, while Cage often emphasized the theatrical or indeterminate aspects of these sonic elements, Dlugoszewski approached them for their pure sonic potential, integrating them seamlessly into her compositions.

Around 1958, Dlugoszewski began developing what she called an “orchestra of 100 invented percussion instruments.” This collection included ladder harps, tangent rattles, square drums, and many other one-of-a-kind instruments, designed and built in collaboration with sculptor Ralph Dorazio, a childhood friend. Her innovation was not just in creating new instruments but in conceptualizing them in sets—akin to the choirs of strings or winds in an orchestra. These percussion instruments were constructed in different sizes and materials, allowing for a wide range of timbral variation. She also developed unique performance techniques for them, expanding the expressive possibilities of percussion music. Initially, Dlugoszewski designed these instruments for herself as a solo performer, but over time, they became a defining feature of many of her compositions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

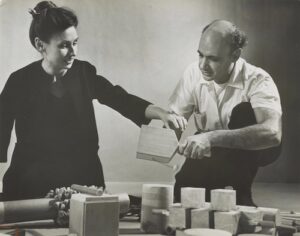

A 40-Year Creative Partnership with Erick Hawkins

Dlugoszewski and Erick Hawkins met in 1950, beginning what would become one of the longest choreographer-composer partnerships in history, lasting from 1951 until Hawkins’ death in 1994. As biographer Amy Beal has noted, their collaboration may be second in duration only to that of John Cage and Merce Cunningham, whose partnership spanned from 1942 to 1992. Together, they created over twenty works and toured extensively, performing across the United States and internationally for decades. Although deeply intertwined artistically, they chose to keep their personal relationship largely private. They married in 1962 but kept this fact hidden from all but their closest friends. It was not until Hawkins’ eulogy in 1994 that Dlugoszewski publicly acknowledged their marriage.

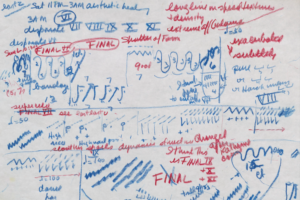

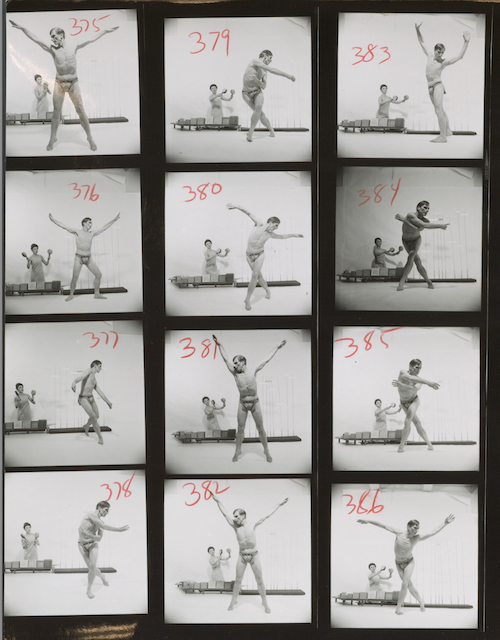

Rather than choreographing to pre-existing music, or composing to fit predetermined choreography, their creative process appears to have been highly collaborative and iterative. It seems that their work often began with prose writings outlining the philosophical ideas they wanted to express, followed by the creation of large-scale structural frameworks that were often complex and asymmetrical. At a certain stage, they would refine these structures into an agreed-upon system of counts and bars, which became the foundation for both the choreography and the music.

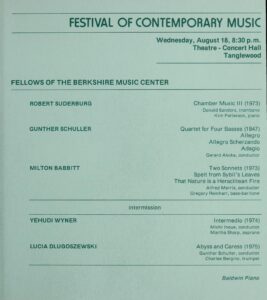

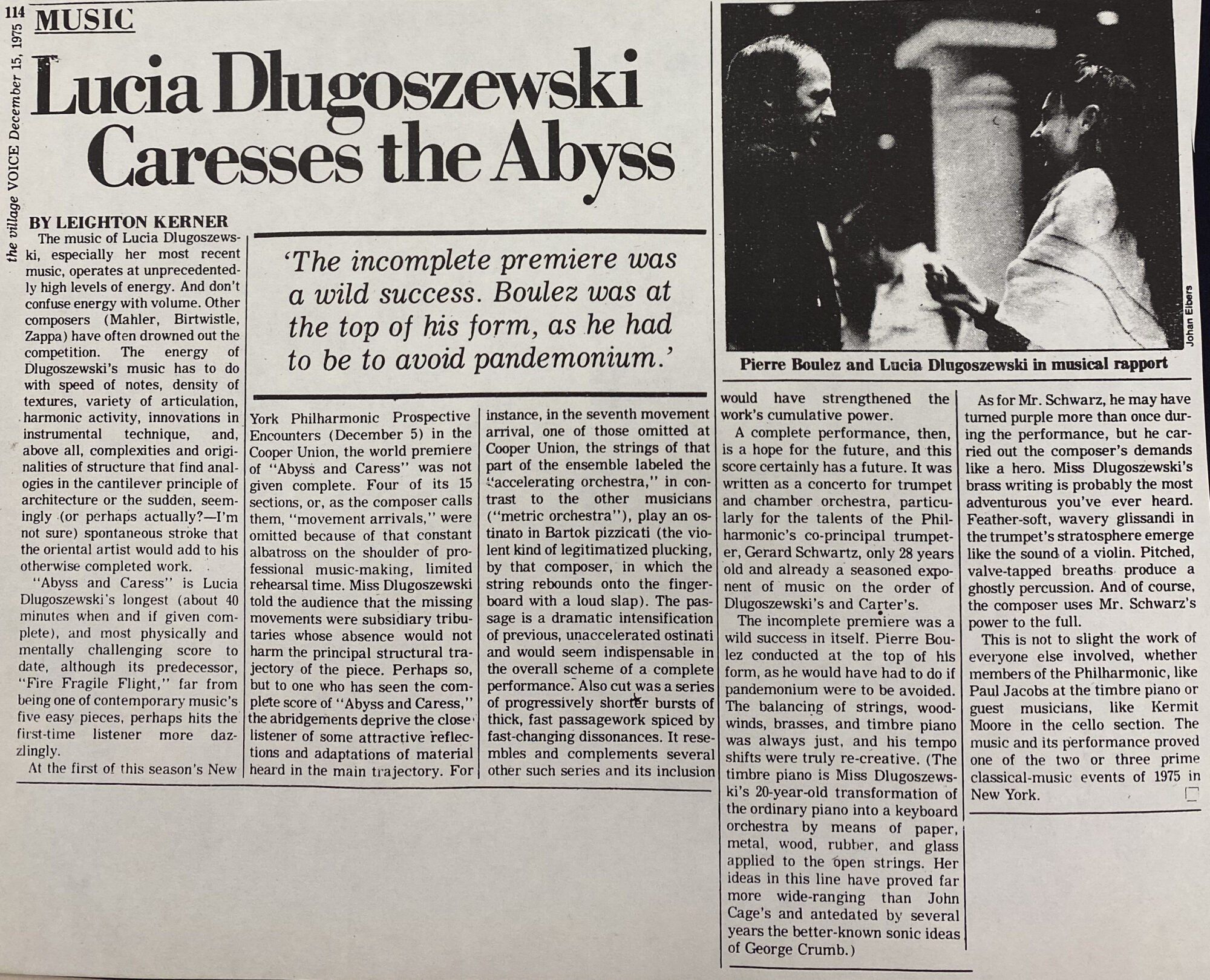

Expanding Beyond Dance: The 1970s and Major Commissions

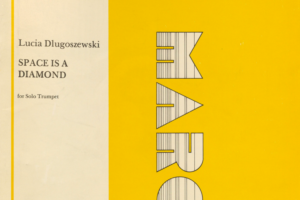

Though much of her early career was defined by dance, by the 1970s, Dlugoszewski was receiving major commissions and building a reputation in concert music. In 1973, she was commissioned by the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Festival to compose Fire Fragile Flight. Two years later, Abyss and Caress for trumpet and orchestra, commissioned for Gerard Schwarz, was premiered by the New York Philharmonic under Pierre Boulez. During this period, she also wrote Tender Theater Flight Nagiere for brass quintet and percussion and Angels of the Inmost Heaven for brass quintet, both composed for the American Brass Quintet. In 1980, the Library of Congress commissioned Amor Empty Elusive August, which was premiered by the Boehm Quintette. Space is a Diamond for solo trumpet and Abyss and Caress were among the few of her works published by Margun, suggesting a promising expansion of her career beyond dance. However, no additional works were ever published.

Space is a Diamond (audio)

Composed in 1970 and performed by Gerard Schwartz on trumpet, Lucia Dlugoszewski’s “Space is a Diamond” is a groundbreaking work that redefined the instrument’s expressive potential. The piece demands an extraordinary four-and-a-half-octave range and incorporates unconventional techniques, pushing both the performer and the trumpet to new limits.

Fire Fragile Flight (audio)

Composed and recorded in 1979, “Fire Fragile Flight” was performed by the Orchestra of Our Time under the direction of Joel Thome. With this recording, Dlugoszewski became the first woman to win the Koussevitzky International Recording Award. The work features an unconventional percussion section with four players on slide whistles, hanging bells, and inside-the-piano techniques. Inspired by the movement of falling leaves in early March in the Great Lakes region, the music incorporates “leap-points” that trigger whirling “startle-juxtapositions” of varying speed, evoking the flickering reflections that can make falling leaves appear to catch fire.

Challenges of the 1980s and a Late-Career Resurgence

Seemingly on the edge of a breakthrough, the 1980s proved to be a difficult decade for Dlugoszewski. According to biographer Amy Beal, her output slowed in part due to long periods spent in Detroit caring for her aging mother, whose declining health required Dlugoszewski’s care for extended periods until her passing in 1988. The stress of balancing family responsibilities with creative work is evident in her journals, as well as in letters from commissioners expressing frustration over delayed scores. Soon after her return to New York, she quickly assumed a caretaker role for Hawkins, whose health was also in decline.

Despite these personal challenges, she composed several major chamber works in the late 1980s and 1990s, including what is often regarded as a major achievement in her catalog, Disparate Radical Stairway Other, a 1995 string quartet commissioned by Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project for Erick Hawkins’ dance piece Journey of a Poet.

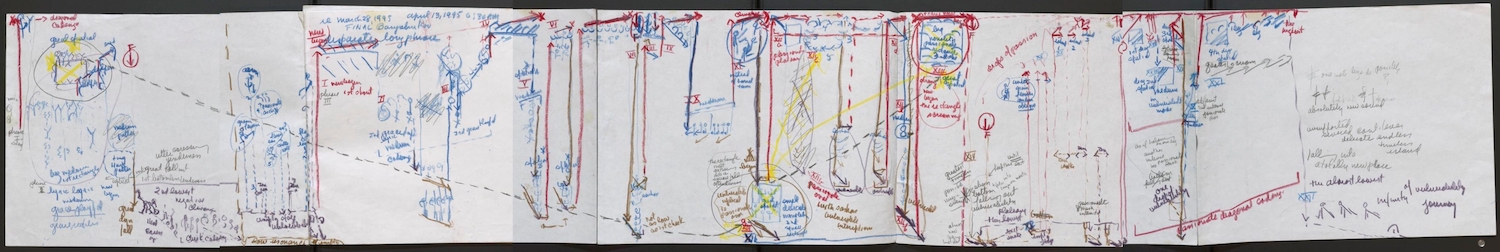

As part of her creative process, Dlugoszewski often created long, scrolling graphic drawings referred to as “Maps,” which depicted the overall structure and key moments of many of her compositions. These Maps reveal an emphasis on timbre and dynamic variation rather than conventional rhythmic, melodic, or harmonic priorities. Intervallic relationships and the ratio of time played a central role in her thinking, with pitch often approached from a timbral perspective rather than a purely harmonic one.

Disparate Stairway Radical Other (audio)

Dedicated to Mikhail Baryshnikov, Erick Hawkins (in memoriam), and Mary Norton Dorazio (in memoriam), this piece was commissioned by The White Oak Dance Project for “Journey of a Poet” by Erick Hawkins. Performed by the White Oak Ensemble—Conrad Harris and Margaret Jones on violin, David J. Bursack on viola, and Dorothy Lawson on cello.

Exacerbated Subtlety Concert (audio)

Composed in 1997 and recorded in 2000, “Exacerbated Subtlety Concert” is performed by Lucia Dlugoszewski on her timbre piano. This work explores similar techniques and sonic interests as earlier pieces but within a distinctly different instrumental context. Recorded on January 17, 2000, at the Summer Center, Concordia College in Bronxville, New York, this performance captures Dlugoszewski’s nuanced approach to timbre and texture through her unique performance practice.

Final Years and Legacy

After Hawkins’ death in 1994, Dlugoszewski became increasingly involved in the Erick Hawkins Dance Company. Named Artistic Director, she took on a more active role in its day-to-day operations. In addition to leading the company’s artistic direction, she became its principal choreographer, creating new works that honored Hawkins’ legacy while reflecting her own artistic vision.

On April 11, 2000, Dlugoszewski passed away in her Manhattan home at the age of 74. That same evening, the Erick Hawkins Dance Company premiered her full-length work Motherwell Amor at the 92nd Street Y. The piece, which she both choreographed and composed, was inspired by the paintings of Robert Motherwell, a close friend of Dlugoszewski and Hawkins. Though her absence was deeply felt, the company honored her legacy by carrying forward the performance as planned.

This project would not have been possible without the support, generosity, and collaboration of so many.

My deepest thanks go to Katherine Duke, who has been an essential partner from the beginning. Our weekly conversations were a constant source of insight. Katherine generously shared her deep knowledge of both Lucia Dlugoszewski and Erick Hawkins, and helped connect us with people, materials, and archives that would have otherwise remained out of reach. Her support touched every part of this project.

I’m also deeply grateful to Libby Smigel and everyone at the Library of Congress for their thoughtful stewardship of the Lucia and Erick archive, and to David Plylar and the Library’s concert team for their partnership. Thanks as well to the many other public and private archives who generously shared materials and information.

To Amy C. Beal—your biography of Lucia was a constant companion and guide. And to Kevin Lewis, whose early scholarship helped illuminate Lucia’s work with percussion instruments—thank you. Renata Celichowska’s book on Erick Hawkins was also an important resource, particularly for its clear and comprehensive listing of his choreographic works.

To the musicians and dancers who brought this work to life: thank you for your artistry and commitment. Special thanks to Agnese Toniutti for her extraordinary work reconstructing Lucia’s early piano pieces, and to Louis Kavouras and the dancers who continue to carry forward Erick’s choreography through their movement.

To Bill Trigg and Hostler Burrows, thank you for your quiet care in preserving the physical traces of Lucia’s percussion instruments. And to Dustin Donahue, for the patient and thoughtful work of creating new, playable versions of these instruments—making it possible for this music to be heard again.

I’m also grateful to our colleagues abroad at Ensemble Musikfabrik and MaerzMusik, including Christine Chapman, Marco Blaauw, Kamila Metwaly, and Monika Żyła, as well as Michał Mendyk, Peter Paul Kainrath, Klangforum Wien, and ImpulsTanz. Your contributions have helped expand the reach and context of this work.

To the many musicians and scholars whose insights shaped this project—especially David Taylor, Rebecca Lloyd-Jones, and Kate Doyle—thank you for the writings and perspectives that informed our thinking throughout.

To the teams at Bowerbird and FringeArts—especially Andy Thierauf—thank you for all the behind-the-scenes work that brought these concerts into being.

To the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage—thank you for supporting this project through its many stages of development.

And finally, to Arin and Dorian, and to all those who offered encouragement, ideas, and support along the way: thank you.

—Dustin Hurt, curator