Philly Native Returns for Two Concert Portrait

by Peter Margasak

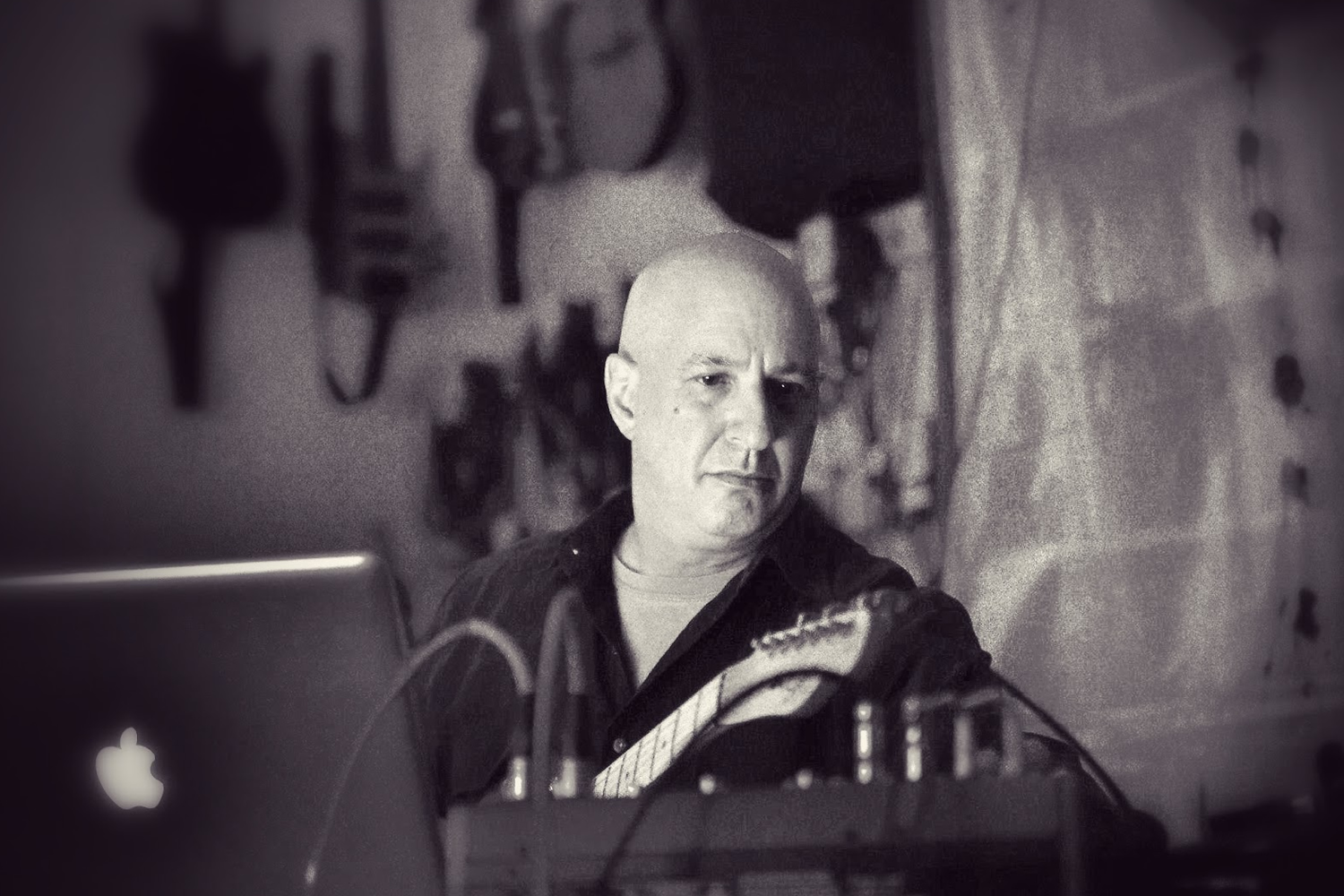

“I’ve always flitted between elements of my artistic agenda,” says Philadelphia native David First, a composer, musician, and bandleader who’s eagerly followed his intense curiosity into an ever-changing array of contexts and approaches over the course of more than four decades. First, who moved to New York in 1984, isn’t a dilettante. Since the late 1970s he’s engaged rigorously with free jazz, post-punk, drones, and minimalist composition, pouring himself into each practice with serious determination, but in a world that prefers to pigeonhole artists into tidy categories his disparate output and his versatility has obscured the fact that a clear artistic through-line has existed in nearly all of his work. As the guitarist in Philly’s visceral, deeply original Notekillers starting in 1976 he coined the phrase “Same Animal, Different Cage” to describe its original repertoire, but that nonchalant motto applies to all of his work since then, too. On Friday and Saturday, February 7 and 8, First will oversee the first-ever portrait concert of his varied career at the Christ Church Neighborhood House, offering audiences an opportunity to understand how all of the various facets of his music fit together.

Over two evenings First will present commissions written for piano, long-form investigations of just intonation, microtonality, and bruising post-punk, including the world premiere of a new composition called “Revolutions” that will bring many of those threads together in a single work, as his New York new music group the Western Enisphere collaborates with the Notekillers for the first time ever. The work will also include experimental video work First has been developing for nearly a decade, creating a kind of visual representation of the properties of just intonation, the tuning system long championed by La Monte Young.

“I’ve jumped around from thing to thing, but it was always in search of that same feeling—a certain electrical charge, certain sensual experience, a certain powerful energy that comes from the friction of elements rubbing against each other that sets off sparks,” explains First, 66. “It can be meditative, it can be psychedelic, it can be raw power energy. With the Notekillers there’s more of an overt physicality to it. We’re all moving around and playing hard, but it’s the same feeling I get when I’m sitting there, trying to zone into a trance—it’s the same result for me. It’s all an attempt to elevate people to some other dimension, some other zone, some other state of being.” Indeed, even in the earliest, crudest work by the Notekillers one can trace a steady fascination with sound as a physical, transformative presence through all of First’s work, whether leading his microtonal World Casio Quartet, playing solo harmonica, or on the extended guitar and electronics explorations collected on Privacy Issues (Droneworks 1996-2009) released by composer Phill Niblock.

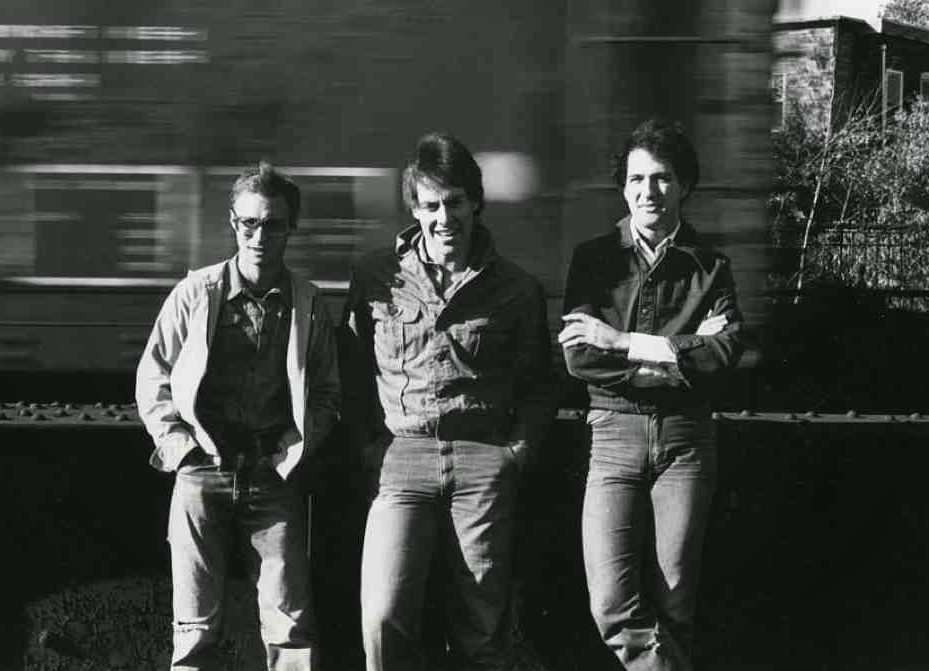

Since the mid-70s First has taken seemingly incongruous routes, whether producing noisy, dive-bombing electronic music, playing with the legendary free jazz pianist Cecil Taylor, or serving as freelance music director of the Trilby String Band in the Mummers Parade. But it was the Notekillers, with bassist Steven Bilenky and drummer Barry Halkin—whose 1980 single “The Zipper” would later be cited by Thurston Moore as an early influence on his band Sonic Youth—that truly launched First’s career as a musician. Still, his subsequent efforts as an improviser, composer, and sound researcher, and have made it clear that there’s much more to his artistry than proto-no wave skree.

“Everything has natural beginnings and endings, and I’ve been lucky to find something else once something ended,” says First, who’s never been at a loss for finding that something else. Surprisingly, he cites rock legend Neil Young as his “role model and biggest hero. There’s certainly a through-line of aesthetics and intent that goes through everything he does. You’ll hear him do the same song with an acoustic guitar, you’ll hear him do the same song with Crazy Horse, or you’ll hear him do it with horns. I remember reading interviews with him early on and every time he would make a turn he would say this is it, I’ve found my thing. And then a year or two later he was onto something else. For a while I felt like that with myself. I never thought I’ll do the Notekillers for a few years and then I’ll do something else for a few years—I just thought that this was it.” In fact, he returned to the Notekillers more than two decades after the trio broke-up. When he learned of Thurston Moore’s admiration, he reached out to the influential guitarist, which led to a powerful archival collection, Notekillers 1977-1981, on the Sonic Youth co-founder’s Ecstatic Peace label in 2004.

Although time has passed, First has maintained a consuming interest in sound as a physical element. You can hear it in the cascading lines of his 1990 solo piano piece “Key Lights in a Palace Balloon” commissioned by Joseph Kubera—which will be performed by Philadelphia pianist David Hughes on Saturday night—as well as his monumental two-and-a-half hour The Consummation of Right and Wrong,” a 2017 electro-acoustic octet piece that will receive its local premiere on Friday night.

The latter work, played by his Western Enisphere—and due for release on Important Records later this spring—represents a breakthrough of sorts. “I fit a whole lot of aspects of my artistic agenda into one piece for the first time—everything from through-composed sections to pure drone sections,” he says. At the same time, he’s continued to make new discoveries with the Notekillers, which reunited in 2004 when the Ecstatic Peace release generated new interest in the group. First would only reconvene the band if it’s focus was on creating new work. The trio will play six pieces spanning the band’s entire history on Saturday’s concert, including a brand new piece, which he says has opened up new possibilities for them.

“That’s one of the few blessings of being an experimental composer is that nobody says you gotta be doing this or that, follow up with this with another thing like that,” he explains. “It’s very comfortable for me. I know it can be confusing to some people. Some people think of me as a drone composer and refuse to really acknowledge the Notekillers and vice versa. And then there are people that think of me as an improviser, that have no idea that I compose at all. The purest fun is the discovery—whether it’s a composition or an approach to playing that I had never thought of before. It’s kept me going. Whether it’s confusing to people or if people will embrace it—I can’t say it’s not my problem, because it’s definitely my problem—but I can’t worry about it too much.”